Recently, I sat at a faculty meeting concerning the upcoming school year (though we’ve just reached the halfway threshold of this one), and a colleague of mine said, “Folks, we’ve got rigor.”

Yep. There it was again. Academic rigor. And though it’s been an education buzzword for years, our teacher-ears perk up every time we hear it. We take it as a compliment. We give it a positive connotation. That’s a good school; it has a rigorous curriculum.

But after that meeting, I went back to my classroom wondering if I really knew the true definition of the word. Because we’ve been studying so much Sylvia Plath in my classes, a copy of The American Heritage High School Dictionary sat nearby on a student desk, and out of curiosity, I took a look.

Here’s what I found.

Rigor, n: 1. Strictness or severity, as in temperament, action, or judgment. 2. A harsh or trying circumstance; hardship. 3. A cruel act. 4. Shivering or trembling, as caused by a chill. 5. A state of rigidity in living tissues or organs that prevents response to stimuli.

This is a word we use to describe a student’s school experience? This is a word we use to describe learning?

What’s even worse, I think, is that we’ve transformed an already unpleasant term (rigor mortis, anyone?) into something else entirely. We’ve determined that the simplest interpretation of the concept is this: rigor=work. We think that by giving them more to do, we are making the curriculum more challenging. It doesn’t take higher level thinking to determine that more work doesn’t necessarily provide higher level thinking.

I started a dialogue with my students about their own learning. One of them said, “At some point, I think it was around sixth grade, school became a big pile of work.” And he motioned with his hands to show the size of the pile; it was almost as tall as he was. And it continues to grow. They feel like they will never reach the bottom. They wonder if the bottom even exists.

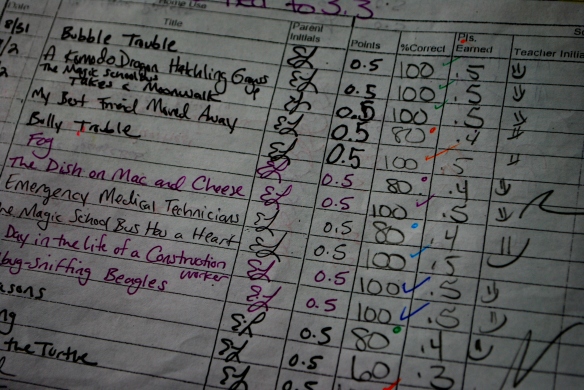

We’ve decided that if they can, they should. They should read before they leave pre-K. They should have nightly homework in kindergarten. In first grade, they should have independent reading goals that require them to read forty books at a fourth-grade reading level in a nine-week quarter. If the curriculum is rigorous enough, by high school, they should be having nervous breakdowns. (If it were an exaggeration, it might be funny.)

Rigor isn’t making our kids smarter. It’s not turning them into thinkers. It’s turning them into machines. They work. They ingest. They regurgitate. And we are concerned only with what they produce: standardized test scores and, subsequently, school grades.

But they do not learn. They do not think. And they do not learn to think. So what are we really teaching them? This: education is a cruel act that causes shivering and trembling and prevents a response to stimuli.

The second part of my colleague’s statement at the meeting that day was something like this: “We need fun.”

We do. And we need to give them back all of the things we’ve taken away. Recess. Field trips. Art, music, physical education, library time. Pats on the back. Empathy.

When my first-grader climbed into the car after school this week, she told me that her favorite part of the day was “Brain Break,” when her teacher turned on music and the students were allowed to leave their seats and move their bodies.

Maybe that needs to be part of the curriculum.