On my first day as a brand-new teacher, a student approached me in the hallway, stopping only when his face was inches from mine, and said, “What the [expletive] are you looking at?”

I had no idea.

And what I mean by that is, truly, I had no idea what (or who) I was looking at. But, moments later, he was sitting in my classroom, and I was supposed to teach him something.

I learned, quickly, that I had to win them over, that the fact that I was standing in front of them with a chalkboard behind me didn’t guarantee their gratuitous respect. If you don’t  know the kids, or don’t care to know them, then you can’t teach them. You can try, but they won’t learn from you. And I don’t mean that you’ve skimmed their cumulative folders. Just because you know that Chris has lived in thirty-six different foster homes by the time he’s sitting in your sophomore English class doesn’t mean you know Chris. In fact, at my very first school, the policy was that teachers weren’t allowed to look at the cumulative folders until they had worked to build some kind of rapport with the kids.

know the kids, or don’t care to know them, then you can’t teach them. You can try, but they won’t learn from you. And I don’t mean that you’ve skimmed their cumulative folders. Just because you know that Chris has lived in thirty-six different foster homes by the time he’s sitting in your sophomore English class doesn’t mean you know Chris. In fact, at my very first school, the policy was that teachers weren’t allowed to look at the cumulative folders until they had worked to build some kind of rapport with the kids.

The problem is that getting to know one’s students takes time. A lot of time. And time is not something teachers have a lot of. Each year brings more demands and more threats (I can’t think of a friendlier word). But wait — we “only work nine months a year” (they always forget to count Sundays and all of those nights during the week) and if we used our planning periods effectively, we wouldn’t have to take all of that work home. Right. Every teacher knows that most planning periods aren’t for actual planning and grading, because no one can do that kind of intensive work in such little time. No, it’s for catching your breath, for stopping  your head from spinning, or (pardon me) using the restroom for the first time all day. And for those of you (us) who have difficulty saying “no,” your classroom might be usurped by high school seniors who happen to have study hall and so your fourth period planning becomes otherwise known as the fourth period “mancave.” (By the end of this school year, after factoring in my lunch bunch, I realized that the only time I was by myself all day was during that one bathroom break.)

your head from spinning, or (pardon me) using the restroom for the first time all day. And for those of you (us) who have difficulty saying “no,” your classroom might be usurped by high school seniors who happen to have study hall and so your fourth period planning becomes otherwise known as the fourth period “mancave.” (By the end of this school year, after factoring in my lunch bunch, I realized that the only time I was by myself all day was during that one bathroom break.)

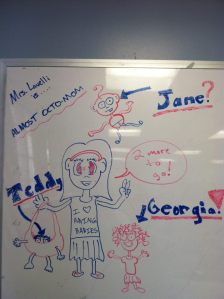

We emphasize standards and benchmarks and results and data and intervention and remediation and learning trends, but what I know now is this: so much of teaching has nothing to do with subject matter expertise. Yes, we want “highly qualified” teachers (oh, Teddy Kennedy, I loved you for your idealism, if nothing else — it seems idealism was inflicted upon your family) and so we jump at resumes with the highest degrees, but none of it matters if we don’t think first about what the kids need in order to learn about being human. And if we don’t focus on that, we’re leaving all kinds of children behind.

They (the people in charge) want us to look at a student and think, “You’re my bottom 25%. How am I going to get you to retain enough to make the required learning gains?” In reality, we look at a student and think, “You have your head down, which means you fought with your dad last night. How am I going to help you feel okay about going home by 3pm?”

New teachers (I was one once) have a romantic idea of what it’s going to be like. They look at the empty desks and imagine well-groomed students (who actually sit in those seats without being prompted) bursting with enthusiasm, filled with inspiration from those carefully-designed lessons. They spend hours and hours decorating their classrooms, making sure the posters are straight, arranging seating charts, creating a Word Wall or a Wall of Fame. (The romanticism tends to subside when you find a pencilled illustration of a penis in the corner of one of those colorful posters, or the ice-breaker that was supposed to take forty-five minutes is over in fifteen because you overlooked the fact that they have all known each other for years and you’re the one they don’t know.) The reality is that the amount of instructional time spent on the actual curriculum pales in comparison to the amount of time spent saying things like: “Please put your phone away”; “No, you may not use the restroom”; “Well, if you pee in the corner we’ll have a bigger problem on our hands”; “Please put your phone away”; “Why do I feel like I teach preschool today?”; “Please pick your head up”; “English! English! You’re supposed to be speaking English in this classroom!”; “Yes, you can start a petition, but I’m pretty sure you’ll still have to tuck your shirts in”; “Please sit down. No, in your seat”; “Please pick your head up”; “Freedom of speech doesn’t mean you can say whatever you want”; “Please put your phone away.”

Now that I think about it, maybe those legislators and new teachers have the same unrealistic idea of what a real classroom is like. They believe that each student has been prepared in exactly the same way, that each student will work to his or her full potential, that if you are a good teacher and you tell them to do it, they’ll do it. If you give them iPads and Smartboards and clickers and laptops, they’ll learn. If they just work hard enough, they’ll pass.

I’m not saying standards and benchmarks aren’t important. Of course they are. And I’m not saying I think students and teachers shouldn’t be held accountable. Of course they should. But what’s just as important is taking the time to nourish and cultivate who these children are as people in addition to percentages.

I’m also not saying that we should go easy on them; we shouldn’t. In fact, it’s easier to be hard on them once you have them on your side; it’s easier to teach the curriculum and expect more from them once you know them. I promise.

I suppose that what I am saying is that along with the frenzy and fear that surrounds AYP, perhaps we should also concern ourselves (just a little bit) with assessing what they’ve learned from us about tolerance and compassion. About decision-making. About confidence and humility.

Because here’s the thing (there’s always the thing, isn’t there?) — it doesn’t always turn out as rosy as The Freedom Writers did. Sometimes, the kid who made you proud by passing that state test gets shot in the head. Or maybe you see his mugshot on the front page of your local paper for killing his two best friends in a drunk driving accident (and immediately, you know who the [expletive] you’re looking at).

And then there’s the day you drive home from work, crying, because you know that you’ll never be able to take the hurt from an aching sixteen-year-old boy, and you think, “I’m not made for this. An effective teacher would know what to do.”

But what would a “highly qualified” teacher do? Would she lock the door and push that kid away, saying she can’t talk to him about his absent father (while knowing he can’t go home and talk about it to his mother)? Would Ms. Highly Qualified say that she doesn’t have the time because she has a five-benchmark summative assessment to design?

Sure, on paper, even I am “highly qualified.” But my question is this: qualified for what?

Earlier this year, when one of my really bright and motivated students told me that he was thinking of studying to become a teacher, my heart broke a little bit for him. For what was ahead. He said to me, “If you were me, would you do it? Would be you become a teacher (again)?”