In an effort to understand my recent infatuation with terrible pop music, I came to an unsettling (to say the least) conclusion: Adam Levine is Justin Vernon’s (Bon Iver) Fifty Shades of Grey. And I am a wretched hypocrite.

Gulp.

Sure, I could blame it on the fact that I never had Sirius Radio installed in the car we bought a year ago. Or that my CD player is broken. Or I could blame it on the kids; it’s their music, right? But when my six-year-old was three, she sangs songs like Ray LaMontagne’s Jolene: “A picture of you holding a picture of me in the pocket of my blue jeans; I still don’t know what love means.”

My current three-year-old sings, “I’m sexy and I know it,” and “I’ve got the moves like jagger.”

Something has happened to me. And I let it. There’s no one to blame but myself. I have fallen prey to the Twilight of the music industry.

I talked to a woman once who told me, “I don’t like to think while I’m reading; I read for pleasure.” And she joked that, as a writer and English teacher, I probably couldn’t understand that. But maybe I can. I mean, is that why I like Katy Perry? Because it’s easy, and I don’t have to think? Or maybe it’s ’cause, baby, you’re a firework.

Maybe I just wish the books that gave us both — thought and pleasure — were the ones that became bestsellers. But they’re not. The ones that sell are the ones that give us everything freely. The ones that have a lexile of 720 (which is roughly the equivalent of a fourth-grade reading level) and gratuitous vampire sex. Awesome. Who doesn’t love vampire sex written in a nine-year-old’s vocabulary? Oh, wait. Me.

Maybe I’m just conflicted. I try to teach my Advanced Placement student to distinguish what is considered a work of “literary merit” from what is not. He is supposed to be reading material with a lexile of 1200, (like Thoreau’s Walden) and I’m supposed to make him “enjoy” it. Meanwhile, his mom (and the rest of the country) is reading the Grey trilogy, which, since it was written first as “fan fiction” (I’m not even sure what that means) in response to Twilight, is probably at the same lexile level. I mean, let’s hope that it’s at least that high.

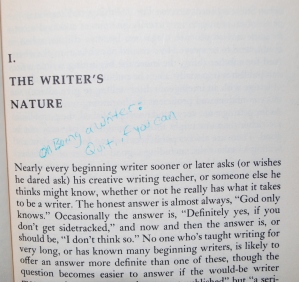

So that must mean that if there is literary merit, there must also be musical merit. And it must be the same for the good-but-undiscovered musicians. Like the poets and novelists who are trying to compose pieces of literary merit and watch as celebrities jump at the chance to turn Fifty Shades of Grey into a film, there are songwriters and guitarists who toil to fine-tune (literally) their craft, who beat themselves up for not “making it big” by the time they’re thirty-four, only to hear One Direction on every radio station. But they have to keep doing it because they can’t not (and, please, I beg you: keep doing it).

I understand, of course, that some of this is a matter of taste. We’re not all going to be drawn to the same kind of music or the same kind of literature. But I think we can all agree that some kinds of composition require more work (on the parts of both the writer and the reader/listener) than others. But we are a culture that loves what’s cheap and easy. And fast. It takes too long to figure out who The Blower’s Daughter (by Damien Rice) is and why the song is constructed the way it is, and we’re too lazy to care whether or not they went through with it in Hemingway’s Hills Like White Elephants.

Hot night. Wind was blowin’. Where you think you’re goin’, baby? (I watched the official Call Me Maybe video the other day and wondered if we’re supposed to believe it took an actual band to create that sound. Or maybe this is one of those cases in which we call upon the willing suspension of disbelief . . . )

I’m not saying everyone has to read Pynchon’s Gravity’s Rainbow or listen to Radiohead’s In Rainbows (although, you probably should). But maybe we could read A Picture of Dorian Gray along with Fifty Shades of Grey and know the difference. Like knowing the difference between Carly Simon and Carly Rae Jepsen.

My bleeding heart is telling me to swear off those mellifluous autotuned voices forever, that I wouldn’t truly be fighting the good fight for artists in general if I didn’t. But I fear a relapse. Would I start dancing on the tables to Justin Bieber (when only Outkast’s Hey Ya could make me do that in the past)? Or what if I became a closet-listener? Like those ladies who replace the jacket of Fifty with the jacket of something more profound, I’d rock out to Payphone in my car with all of the windows up.

But maybe it’s worth the risk. Maybe, as an artist (am I an artist?), it’s the right thing to do. If I’m going to make the investment, I want to invest in those who invested themselves in the first place. (I sort of envision all of us raising our pens and guitars and paintbrushes and drumsticks in the air as we revolt.)

And so, in the way that I have refused Stephenie Meyer and E.L. James for their cheapness, for their easiness, I refuse you and your mindless but oh-so-seductive ways, Adam Levine. And, really, what’s wrong with thinking, anyway?

As I write this, that same three-year-old is singing along with Justin Vernon, “And I told you to be patient. And I told you to be fine.”

My, my, my.